Erin Welke-Martens knew long before she completed her nursing education that when you work in your own community, your patients are your neighbours, friends, and family.

“It’s an incredible feeling to walk into a delivery room and the patient says, ‘oh you look exactly like your mother!’,” says Welke-Martens, a Registered Nurse. “My mom was the lab supervisor at the hospital in Pincher Creek for more than 20 years, and our family has been farming the land in the area for even longer.”

When Welke-Martens had the opportunity to return to Pincher Creek after graduating from the University of Alberta’s nursing program, she felt like she’d won the lottery.

“I was fortunate enough to have completed my final preceptorship in Pincher Creek, and when a position became available, I was thrilled to accept it,” says Welke-Martens. “I had such a wonderful learning experience during my preceptorship, and after training in a large city hospital, I really felt like I’d come ‘home’ with rural nursing.”

One of the many things Welke-Martens appreciates most about practicing in a smaller community is the variety of care she gets to give each and every day.

“You get to be every kind of nurse in one day. It can be overwhelming at times but it’s such a special opportunity to have. I might be giving end of life care for a patient at the beginning of my shift and then bringing life into the world by the end of my shift,” says Welke-Martens. “In bigger centres, it can be easy to feel like just another nurse but in a rural setting, you’re often ‘it’. It’s you and there’s no one else.”

While being ‘it’ comes with moments of elation, it often comes with its fair share of lows.

“When I was 30 weeks pregnant, I was part of the trauma team who cared for a young child who died as the result of a tragic accident,” says Welke-Martens. “The stress of caring for this child and his family led to my being put on bedrest for threatened preterm labour and I was not able to return to work prior to the (safe) delivery of my child. I struggled with anxiety and flashbacks related to this case prior to, and following my son’s birth and especially leading up to my return to work.”

That anxiety was put at ease after Welke-Martens attended a continuing medical education course brought to Pincher Creek by RhPAP.

The CARE Course was designed by two rural physicians from British Columbia, Dr. Jel Coward and Dr. Rebecca Lindley, who were sought out to come up with an educational experience that was led by rural physicians, for rural physicians.

“Rural providers have a very wide scope of practice. Working in a rural emergency department means being prepared for anything to come through the doors,” says Lindley. “A rural team is small. When a patient is critically unwell, there is not a large team that comes running in to assist. Given this small team, the need for excellent teamwork and inter-personal skills is accentuated.”

This sentiment is echoed by Welke-Martens’s colleague, Pincher Creek physician, Dr. Gavin Parker.

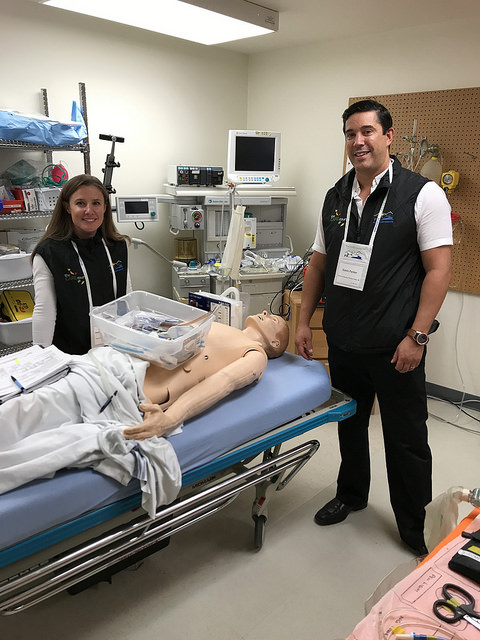

“The CARE Course is tailored for your community’s needs and is run in your own facility. Continuing medical education budgets are tight for a lot of healthcare professionals so being able to attend a course on the weekend, in your own city and experience it with your own healthcare team is rare,” says Parker, who is also an instructor for The CARE Course, and an RhPAP board member.

“It’s great that RhPAP sees the value and supports funding these opportunities for learning. Getting to learn alongside your colleagues improves communication between everyone which is vital in high stress situations.”

For Welke-Martens, the hands-on learning sessions provided a safe environment for her to regain her confidence and refresh her skills.

“Because there’s no formal testing in The CARE Course, you don’t have that added pressure of failing like you do with other acronym courses,” says Welke-Martens. “The scenario-based setting allows you to just relax, concentrate on learning and gives you the freedom to ask as many questions as you like.”

Exploring High Acuity Low Occurrence (HALO) scenarios in a safe learning environment also allows for failure, which is a good thing says Parker.

“Even the most experienced doctor, nurse or paramedic has that feeling of doubt and inadequacy when presented with an unfamiliar situation,” says Parker. “Getting comfortable with that failure is important and something I try to impart when I’m teaching. The learning outcomes that occur from failure are often the ones that are the most valuable and resonate the most with healthcare professionals.”

Welke-Martens enjoyed her experience so much she’s hoping to be involved in teaching of The Care Course in the future and hopes more opportunities like it come to rural communities in the future.

“It’s always so lovely to hear from friends or family members who will tell me about a friend of theirs who I cared for,” she says. “Getting to care for your neighbor, family friend or someone from your community is such a privilege. It really matters what you do and the care that you provide.”

- Article & Photos by Meagan Williams