“Cooking is all about connection”

– Michael Pollan

In order to learn more about the Low German Mennonite (LGM) population, also known colloquially as the “Mexican Mennonites,” I attended a conference in Taber, hosted by the Southern Alberta Kanadier Association (SAKA), and funded by Family and Community Support Services (FCSS).

During the past 20 years, Low German Mennonites from Mexico have become part of the social fabric of rural Alberta. Their traditions have influenced rural communities, and their impact on the revitalization of several towns and villages throughout the province cannot be understated.

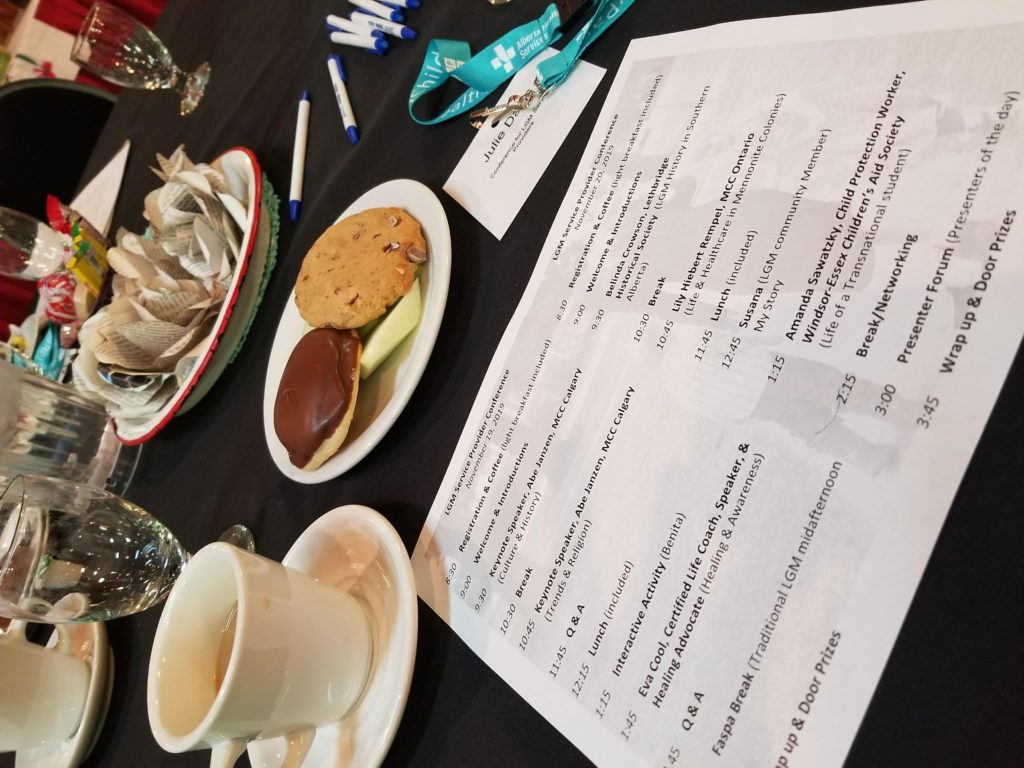

The conference room in Taber is packed. Health, education, and social service providers from across Southern Alberta are gathered here to explore the cultural practices, perceptions, and values of the Alberta LGM population in order to better serve and meet the needs of this population.

Since food is a great introduction to language and culture, we start the day with an LGM food quiz.

I quickly realize how much I don’t know much about my rural LGM neighbours.

My Family and Community Support Services LGM tablemates—a counsellor, a family support worker, and a parenting and family coach—are very open about sharing their LGM experience. I tasted Kyringle, a braided bun dough, and have become a fan of Faspa, a light meal in the afternoon. My new friends also share tips to make a creamy Kielke, the white sauce that goes over the noodles we eat for lunch.

Learning about the names and journey of these foods, I begin to wonder how LGM families came to settle here in Southern Alberta?

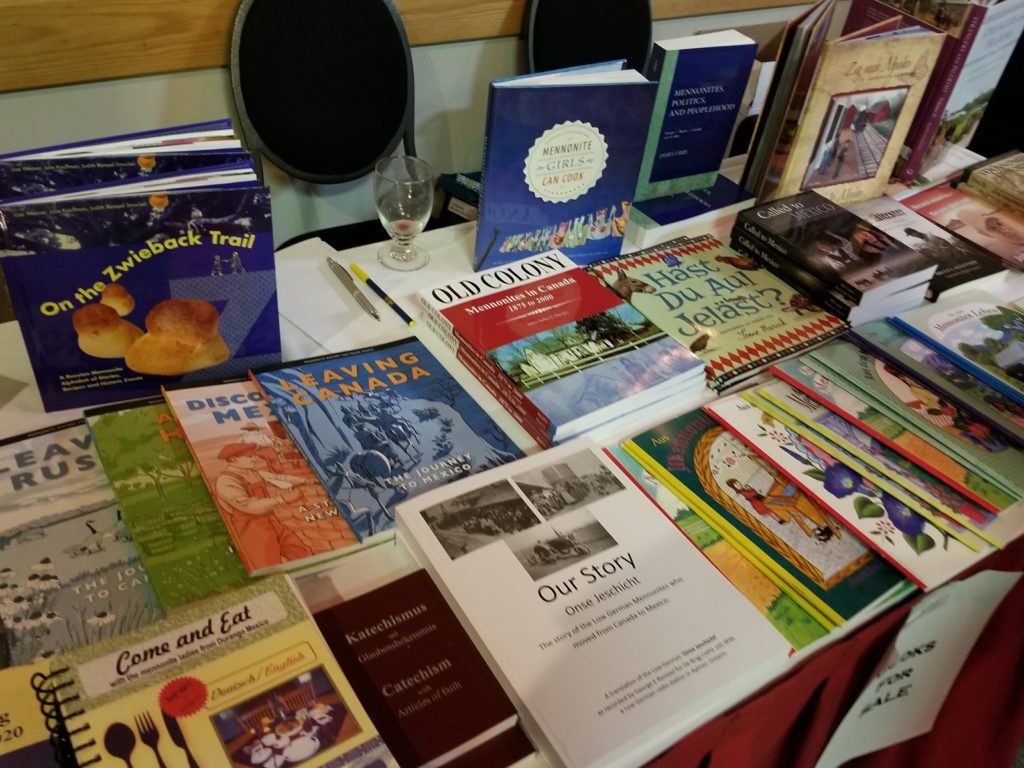

Tracking LGM’s journey

Mennonites originally came from West Prussia and settled in Russia in the late 18th/early 19th Centuries. “Old Colony” refers to the Mennonites settlements in Russia. “Old Colony” is also used as a church denomination, representing the largest visible Mennonite denomination. In some locations, they are called Reinland, Chorititz, Sommerfeld, or Bergthlaler.

After 1873, some 7,000 Old Colony Mennonites left the Russian Empire and settled in Canada. In the period leading up to and during the First World War, governments in Manitoba and Saskatchewan passed laws requiring compulsory attendance at public schools.

In response, the Old Colony Mennonites sent delegates to other countries to seek out new lands for settlement. They negotiated with the Mexican Prime Minister for a tract of land in Northern Mexico. In 1922, approximately 6,000 Mennonites left Manitoba and Saskatchewan for Mexico.

Between 1922 and 1925, some 3,200 members of the Reinlaender Gemeinde from Manitoba and 1,200 from Swift Current left Canada to settle in Northern Mexico in Chihuahua while about 950 Mennonites from the Hague-Osler settlement in Saskatchewan settled in Durango. By 1927, some 7,000 Mennonites from Canada lived in Mexico.

By the 1940’s, many LGM families began arriving in Ontario and Manitoba for seasonal work, owing to drought, overpopulation, a lack of land, and a devalued peso in Mexico.

Southern Alberta was not a first choice until the 1970s, when plentiful, labour-intensive, seasonal work opportunities became available in the sugar beet industry, area feedlots, and on dairy and potato farms.

In 1994, NAFTA allowed temporary workers access to the Canadian labour market, which meant more rapid migration for seasonal work. This trade agreement, alongside agricultural expansion fueled by irrigation, resulted in heavy immigration in around Taber, Coaldale, and Grassy Lake.

LGM workers were contracted on farms during the warm part of the year. At that time, the housing provided to contract workers on farms tended to be cold, so, since there was less work and it was cheaper to live back on a colony in Mexico, workers returned to Mexico in the winter. Going back and forth was a good way to optimize finances and better preserve LGM traditions. Housing became more available in the 1990s, and, by 2000, many of the LGM families were living year-round in Southern Alberta.

Worsening poverty, water shortages, and drug-related violence across Northern Mexico encouraged significant numbers of Mennonites living in Durango and Chihuahua to relocate to Canada and other Latin American countries. Between 2012 and 2017, it is estimated that at least 30,000 LGMs immigrated to Canada.

Education and health care: Collaborating with LGM families

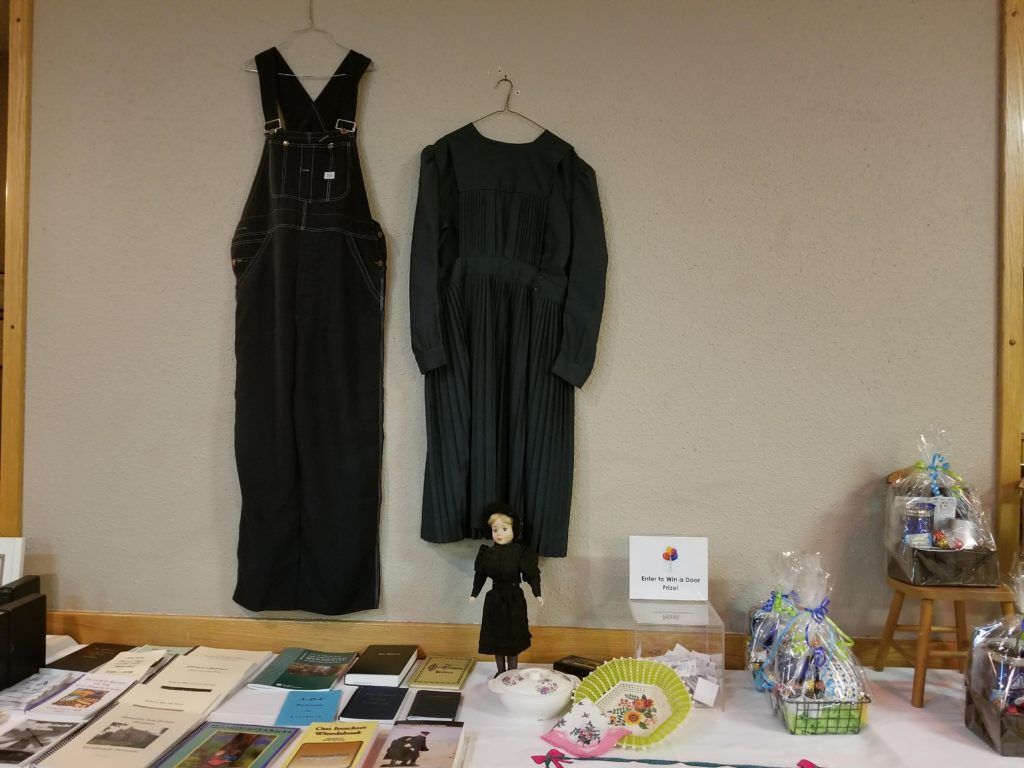

Historically and culturally, the “Old Colony” encouraged communal living, which meant encouraging those skills and trades that supported community building and communal living.

In the early seasonal migration period in Canada, it was common for LGM children to help their parents on the farm, while being homeschooled in Southern Alberta to meet their spiritual and cultural learning needs. In recent years, local school divisions have recognized the interests and values of the LGM population by adding religious classes, programs, and LGM school assistants to their schools.

One of the conference’s speakers, Amanda Sawatzky, an LGM child protection worker at Windsor-Essex Children’s Aid Society in Ontario, spoke about her experience pursuing education supported by her progressive LGM parents and her life as a transnational student. Sawatzky spent kindergarten to Grade 12 in a mix of schools including: Mexican colony; Mexican public; and Ontario public schools. Until Grade 10, she attended at least three different schools each year.

She spoke of the integration issues experienced by LGM students. These challenges include not only changing from colony to public schools (and often back), but also adjusting to different cultures, new languages, different values and dress codes.

Lily Hiebert Rempel, from the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Ontario, spoke about life and health care in Mennonite colonies1.

Possessing a background in Public Health, Hiebert Rempel emphasized the importance of supporting and encouraging LGMs to complete high school and to enter the health professions.

LGM health-care providers can help provide informed voices in community health-care discussions on topics such as medications, the value of immunizations, and when to access pre-natal care. They would also encourage LGM perspectives and culturally safe environments for this population within the health system.

Overall, providing culturally safe health promotion and education will enhance this community’s capacity to make informed health-care choices for themselves and their families.

Many thanks to the LGM speakers and LGM attendees who were very warm and open in sharing their experiences and opportunities to support the LGM population in Southern Alberta. I hope to have the opportunity to learn more and connect with this rural population in my role with RhPAP.