He might just be the most interesting man in rural medicine.

Dr. George Stewart-Hunter has raced cars, killed the world’s most dangerous animal, piloted his own plane to the Bahamas, and just bought a new motorcycle.

And, at 96 years, he’s still practising in long-term care at the Vermilion Health Centre — specializing in geriatrics.

“You want to be a what?”

Dr. Stewart-Hunter has become quite the trailblazer after declaring to his father he wanted to become a surgeon.

“‘A what?’” exclaimed his father.

“At age eight, surgeons don’t [really] exist, but I never changed [my mind],” chuckled Dr. Stewart-Hunter, as he recalled the conversation 88 years ago that sparked the beginning of a storied career.

Since then he’s been working more than seven decades in some of the world’s most interesting — and often dangerous — places.

His specialist training began in the Royal Air Force’s medical section near the end of the Second World War, after telling his commanding officer, “all I want in life is to do surgery.”

The 23-year-old trained for about six months alongside a London University surgeon and then was suddenly posted near Singapore where the war continued to rage. He wasn’t even officially designated a surgeon.

“On the last day, before I was leaving Britain, my mentor sent for me and said, ‘I’ve done you a favour, I have pushed it through and you are now a graded surgeon in the air force.”

Dr. Stewart-Hunter arrived in the Far East, dismayed that they already had a surgeon. He was eventually assigned as the air force’s only obstetrician/gynecologist in the region to support civilians as well as military.

“I’ve only got three weeks experience in gynecology,” pleaded Dr. Stewart-Hunter, then in his mid 20s. “Well, you’ve got three weeks more experience than anybody else,” replied the commanding officer. They agreed to support him at a nearby hospital where he arrived ready to learn.

“Your’re a doctor, thank God. Deliver that baby…”

Instead, Dr. Stewart-Hunter was thrown right into service when he was met by a frantic nurse who recognized his medical badges and immediately said, “You’re a doctor, thank God. Deliver that baby, I’m busy,” and disappeared.

“I knew enough that I got the baby out, and everything was fine. Then I got a tap on the shoulder and someone said, ‘I’ll do the afterbirth, you get into Room 7,’ and it went like this the whole day. I delivered over ten babies on that day — all complicated.”

About three years into his Far East service, he became a seasoned obstetrician/gynecologist. He eventually also officially qualified back in Britain, but kept his hand in at the surgical unit as much as possible.

In the mid-’50s, Dr. Stewart-Hunter was asked by the University of London to help set up a medical facility in Nigeria. Within a year, he returned to Inverness, Scotland, after believing his East African term was up. In reality, he’d passed his Nigerian posting with flying colours and they wanted him to continue. True to his word, he kept his new role in his native Scotland.

Looking back, it was a good career, and life, move.

“Otherwise, I would possibly be dead,” says Dr. Stewart-Hunter, as a few years later revolts in Nigeria resulted in four doctors murdered and the wounding of several others.

He later spent time in Kenya and Nairobi practising obstetrics and gynecology, while car racing, flying, and pursuing other interests in his spare time.

Coming to Canada

Dr. Stewart-Hunter arrived in Canada in 1968 with brief, but challenging, stints in Northern Alberta communities.

It was his destination, and clearly his destiny, when he piloted his own plane to Vermilion about 40 years ago to practise.

“(Vermilion) seemed to be ideal because it was a mixture of surgery and obstetrics. It was clouds all the way until I reached the east side of Mannville and all of a sudden there was a great circular clearance and in the middle of it was Vermilion, basking in the sun.”

Fifteen to 20 years ago, Dr. Stewart-Hunter retired on a British Columbia sailboat. He continued to keep up to date with medicine, but retirement didn’t have quite the same appeal that 50 years of obstetrics, gynecology and surgery brought him.

A chance seminar on geriatrics/palliative care was all it took to draw him back to Vermilion.

Out of retirement, to work with the retired

After spending time in Britain, France, Germany, and Italy learning about palliative care, Dr. Stewart-Hunter started a unit in Vermilion with three other physicians.

“Geriatrics, yes, it is complicated, with multiple diagnoses and multiple drugs which are going to react with each other … Sometimes, leaving things alone is the best option, because the cure is worse than the disease.”

Dr. Stewart-Hunter loves the challenge of tweaking treatments to benefit his patients, popping in to check on his patients often seven days a week.

“You’ve got to treat them as human beings… they can still feel pain – mental and physical,” Dr. Stewart-Hunter explains. “Our team here is one of the best I’ve ever worked with.”

He ponders whether his age and life lessons bring a different perspective to his patients, ranging in age from the late 50s to more than 100 years.

“We do appreciate more as we get older,” he says.

“I’m 96, and I’m very lucky. I still walk, I just bought a new motorbike … I go out every couple of months to the coast to visit my kids alone. I go down to the southern United States for seminars on my own. The only thing I can’t do now is lift my carry-on case [into the aircraft overhead bin].”

A genuine love for people

Patients, staff, and visitors get to enjoy another one of his passions as they walk down the hospital hallway where many of his framed paintings are on display. Once a month, he teaches painting classes to residents.

For five years, resident Catharina Landry has enjoyed kibitzing back and forth with Dr. Stewart-Hunter.

“He’s just fun and always doing something, saying something,” Landry says. “It makes life a lot easier. He’s always around here. We are lucky to have him.”

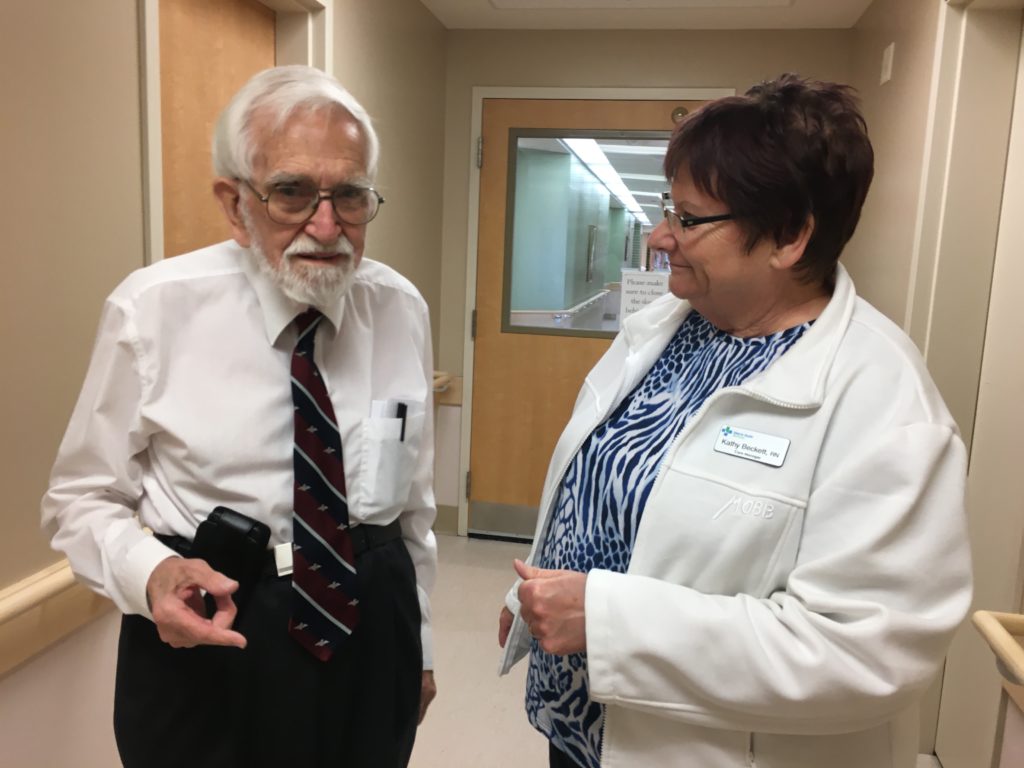

Long-term care manager Kathryn Beckett agrees and says that his patient commitment and respect for the health-care team is second to none.

“You can see he cares about these residents,” says Beckett. “He is the old school of doctor … He went into it because it was of way of life, a calling. He knew from [age] eight that he wanted to be a doctor. It’s a little bit different mindset.

“To him, it’s a privilege [helping these people].”

- Article and photos by Lorena Franchuk