Remembrance Day continues to stir memories for retired Canadian Armed Forces members Linda Parrish and Mark Simons. The veterans, who now work in rural health care, think about those they served alongside and remember the lifelong friendships they forged and pay tribute to their fellow comrades who died in service.

— Photo supplied by Mark Simons

•••

What could a landlocked southern Alberta town have in common with a Royal Canadian Navy ship in the middle of the Pacific Ocean?

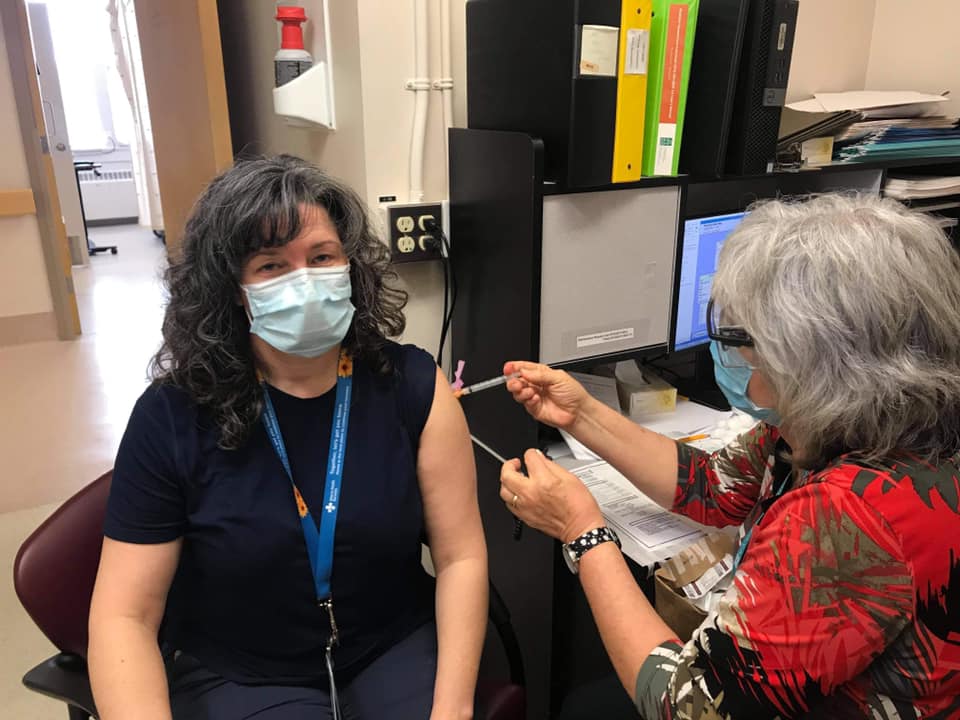

Retired Petty Officer 1st Class Linda Parrish from the Canadian Armed Forces can draw some parallels after working in both settings as a physician assistant.

– Photo supplied by Linda Parrish

“Moving to a rural environment, [the military] really helped to prepare me for the isolation, to be able to make decisions fairly quickly under stressful situations, and to work with a really small crew,” said Parrish during a break at the health centre in the town of Bassano, two hours southeast of Calgary.

“You really get to know your team on an intimate level. You learn each other’s strengths and weaknesses, and you learn to adapt so those holes get plugged, and the patients get the care they need,” said Parrish, who spent 25 years in the military with both the army and the navy.

“I’m actually working with more health-care professionals here [in Bassano] than I’m used to [working with] in an army or navy environment,” she added.

It wasn’t uncommon for Parrish to work on her own or with another Canadian Armed Forces paramedic caring for upwards of 250 service members.

The type of cases she deals with in Bassano vary considerably. Parrish sees both male and female patients from infants to seniors with a variety of issues. This context is in stark contrast to the military, where the bulk of her cases were healthy men aged 18 to 55 years requiring acute and orthopedic care.

“You really get to know your team on an intimate level. You learn each other’s strengths and weaknesses, and you learn to adapt so those holes get plugged, and the patients get the care they need.”

– Physician Assistant Linda Parrish, who retired as a petty officer 1st class after spending 25 years in the military

In Bassano, her scope of practice is broad, involving acute, emergency, long-term, and outpatient care.

“I have my own scheduled patients in my outpatient clinic … and a physician will either audit the clinic chart, or we will have a conversation about … that patient, depending on what the patient’s needs are,” said Parrish.

“There are many things that [physician assistants] do at elbow [or alongside the doctor],” she said. For example, a physician could benefit from a physician assistant’s clinical expertise while setting a bone fracture or helping to manage a patient’s airway during sedation.

“My education is not as extensive and certainly not as long in duration or in complexity [as a physician], but it’s based on the same medical model. The way we practise medicine is designed to be complementary.”

Both physicians and physician assistants are regulated by the College of Physicians & Surgeons of Alberta (CPSA).

The military has trained physician assistants for decades, but they are not as visible in public health care as some other health professions. Parrish estimates there are more than 30 working in Alberta with the bulk of those physician assistants working alongside medical specialists in urban clinics.

– Photo supplied by Linda Parrish

According to the CPSA website, 800 physician assistants work across Canada. While the military used to be the only place to train as a physician assistant, four universities now offer the degree program in Canada.

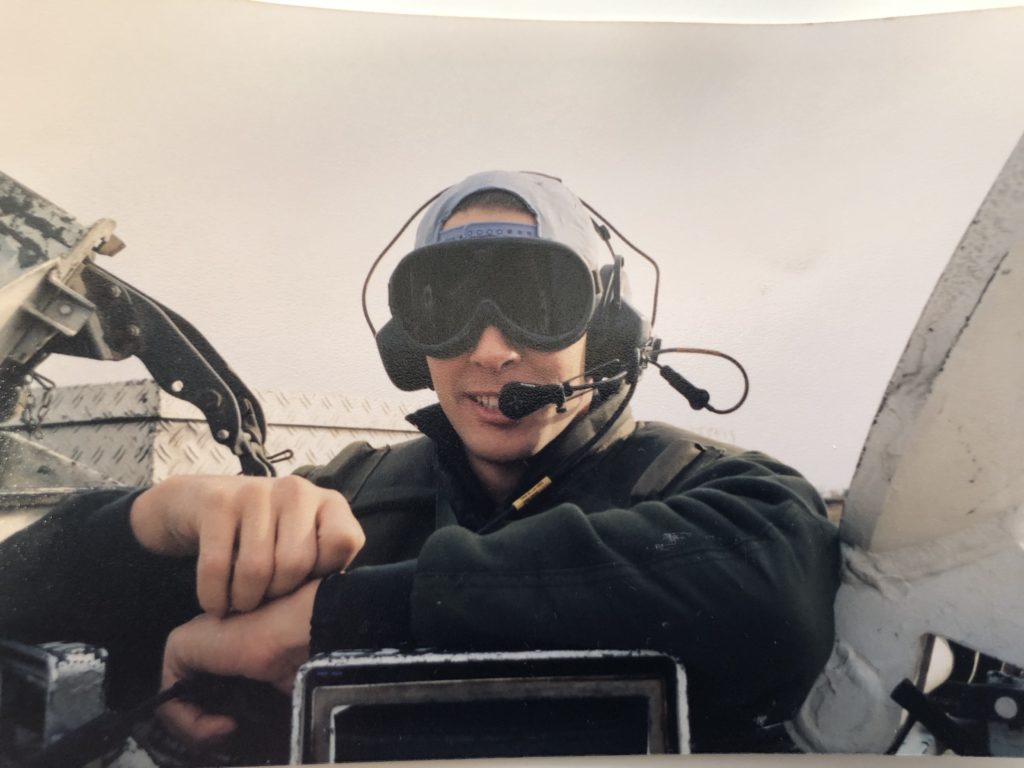

Retired Warrant Officer Mark Simons is another physician assistant whose military experience has benefitted rural Albertans.

Both he and Parrish were hired eight years ago when the first physician assistants were introduced in Alberta to improve patient access to health care.

Simons, who started in the military reserves in 1985, retired from the military after recognizing that maintaining his clinical skills at his base in Gander, N.L., with its low number of patient cases, was challenging.

“There were only 60 military people on base, and they were all very healthy, because it was a search and rescue base,” said Simons. “I would see maybe one to two people per week.”

It was a chance call with a friend, who was involved in physician assistant recruitment, that led to his move to Alberta.

“I was on the phone gabbing with him, … and I said, ‘I wish there was a spot in Alberta like Milk River.‘ He said, ‘did you say Milk River? And I said, ‘yeah’ and he says, ‘when can you start?’”

Finding and retaining physicians in Milk River has been tricky in the past, so having medical staff with ties to the region, like Lethbridge-born Simons, helps maintain health-care continuity.

– Photo by Darryl Essen

Simons said it can be overwhelming for one doctor—especially those new in their careers—to be responsible for such a large area, stretching as far north as Warner to the U.S. border 23 km to the south.

Possessing a large retirement community and surrounded by agricultural land, the town of Milk River is serviced by Dr. Henry Omamuyovwi Ovwasa, Simons, and a locum [temporary replacement] doctor who fills in as needed on weekends.

Simons embraces his role as a physician assistant. He believes this role is “made by doctors, for doctors,” with duties differing depending upon the needs of the physician and the patients.

“I did what I had to do, but you … love these guys. They were 10-feet tall and bulletproof. They saved lives everyday—Canadian lives, Afghani lives. They were doing something they believed in, and they were heroes, every one of them.”

– Mark Simons, a retired Canadian Arms Forces warrant officer who left the military to practise as a physician assistant in Milk River

In Milk River, Simons concentrates on family medicine with Dr. Ovwasa supervising and stepping in as needed.

“I see patients, prescribe medications, order tests, and get the results of the test back. When it’s something complex … where I [don’t] feel comfortable anymore, I go down the hall to [Dr. Ovwasa] and … say ‘what do you want to do with this?’”

Simons fondly recalls his military days which spanned tours in Afghanistan, Yugoslavia, and many postings across Canada. What he doesn’t miss is his leadership role in Afghanistan as warrant officer, especially when he needed to make tough decisions on who to send into the active fighting regions to provide medical support.

“I think about their eyes, the faces of my [troops] coming back, and they were so burnt out, because the day-to-day stress of wondering if your vehicle is going to get [hit by the enemy], wondering if [you’re] going to die and if you’re going to die in a horrible fashion.”

Many shifts were back to back, especially when the medical team was short members.

“[The troops] would come back from one patrol and, often, I would meet them in the compound. I [would] take their jump bag [backpack with supplies], and walk back with them to the shacks. I would say ‘OK, get a quick shower and, then, we will go down to the mess hall [to] get a meal, but, then, [I need] to get you to go again.’ They never, ever said no,” he recalled.

While he understands it was his job, Simons said he still feels a level of guilt about dispatching his troops into danger zones.

“I did what I had to do, but you … love these guys. They were 10-feet tall and bulletproof. They saved lives everyday—Canadian lives, Afghani lives. They were doing something they believed in, and they were heroes, every one of them.”

Simons is content to remain in his current physician assistant role, serving on the front lines in rural health care.

“I miss being a troop, I do. I will miss it for the rest of my life. It is the greatest job in the world.

“Being a physician assistant is fantastic—I just want to see patients and be a physician assistant.”