The pastoral prairie around Alliance was quiet long before COVID-19 required citizens to social distance.

This scenic village, situated near the Battle River, is well over an hour from larger urban centres, an isolated location that has helped it weather the COVID-19 storm.

Indeed, Alliance, and surrounding Flagstaff County, have been incredibly successful at keeping the curve not just flat, but non-existent, having registered no cases of the coronavirus thus far during the outbreak.

While the community’s relative remoteness from larger centres has helped to keep COVID away, Alliance’s location wasn’t enough to protect it from a similar outbreak a century ago—one which proved far deadlier.

As the First World War wound down in Europe during the fall of 1918, the Spanish flu arrived in Canada with returning troops and spread quickly, afflicting communities across Canada.

“It spread across Canada very quickly, because there was a troop train … loaded up in eastern Canada, going across the country [carrying] soldiers [who] started getting sick,” said Suzanna Wagner, a history Master’s student, who researched the Spanish flu and its impact on Edmonton’s University of Alberta, where severe cases were treated.

“Obviously, [the soldiers] were infected when they got on the train, and as the train went across Canada, it would stop, and the sick soldiers were sent to local military hospitals,” she said.

The virus crossed the nation in just one week in October 1918, at a time when spitting in public was socially acceptable and handkerchiefs a quintessential accessory–not necessarily cleaned very often– making it relatively easy to transmit the respiratory disease, Wagner said.

The flu quickly left behind its mark as railway workers and soldiers interacted with locals along the way.

Alliance was no exception.

There are no records on how the flu arrived in the agricultural community, but the village of 200 residents at the time (home to about 160 people today) was hit hard, according to Phyllis Alcorn, a lifelong area resident, and author of In the Bend of the Battle, a history book depicting life near the Battle River.

The Alliance School was quickly converted to a hospital, with beds and bedding donated by the local hotel owner.

“The town [was] kind of closed off and, if you needed groceries … or staples from town, you came to the edge [of town] and someone met you there,” said Alcorn, noting it was similar to curb-side pickup from stores and restaurants today.

[The pandemic] was five times deadlier than the war…

– News report about the Spanish Flu

Dr. Russel Boyle, the village’s doctor, caught the deadly flu shortly after the pandemic began, and succumbed quickly on November 18, 1918.

“[The Alliance area] had no cemetery, but they quickly made one … in the fall and the first one [buried] was a baby … he was three months old,” said Alcorn. Two additional area residents died around the same time.

“[The pandemic] was five times deadlier than the war,” the news reported at the time. An estimated 50 million people died across the world in the 1918-1919 pandemic, with more than one-third of the world’s population infected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

By late December 1918, the virus appeared to peter out in Alliance. That was until the local Argyle Women’s Institute held a bazaar at the rurally located Argyle School three months later.

“It was a big deal,” said Alcorn. “The community people all turned out and somebody had come in on the train and attended. That’s how [the flu] spread to everybody. Within the next few days, it was in every household.”

Local residents volunteered to nurse the sick, mind children, prepare meals, and do endless chores when they heard of any households infected; however, sometimes, word didn’t get out in time as telephones weren’t widely available in the country just yet, said Wagner.

“You had to stoke your fireplace or you would freeze,” she added, noting running water wasn’t always available. “There are stories about people who would walk miles to check on people and their animals … but you were a lot more alone, you were a lot more in danger [back then].”

Alliance’s one-room school became a full hospital again with as many as 40 patients being treated during the 1919 spring outbreak. Others convalesced in people’s homes or on their own.

Rural communities like Alliance were hit particularly hard as access to transportation, communication, water, and supplies, and a shortage of doctors and nurses were issues.

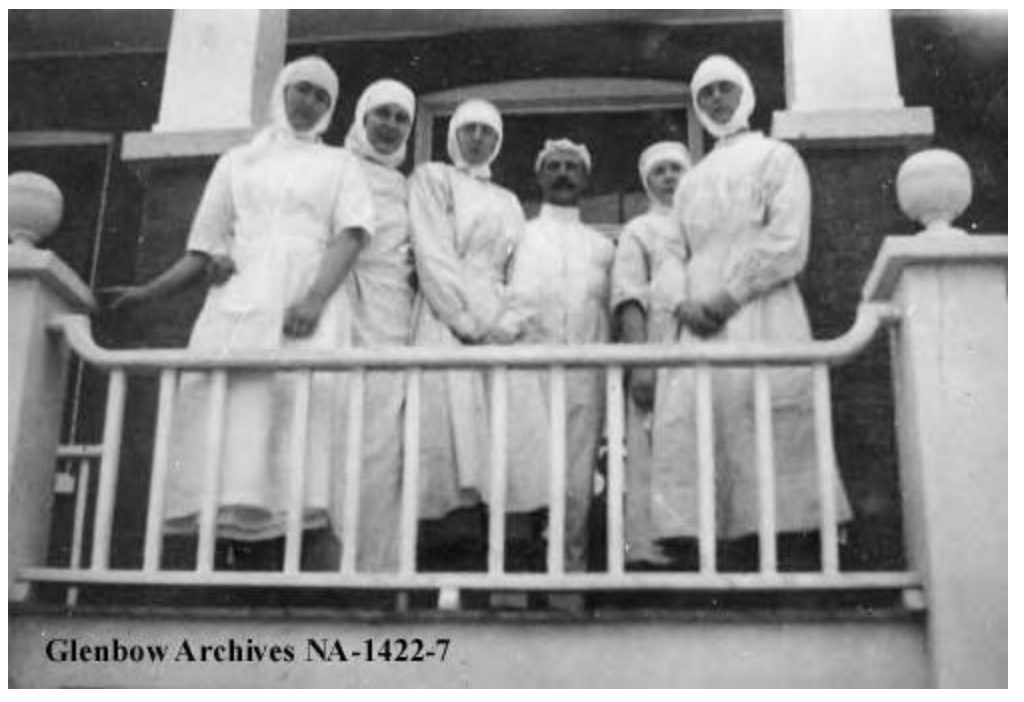

Photo supplied by Glenbow Archives.

“The impact on rural communities, particularly in the north, was truly devastating,” said Trudy Cowan, author of the children’s book QUARANTINE: Keep Out! based on the early 20th-Century influenza.

“There were reports of whole … communities dying … with no one left to bury them … There were few or no medical personnel. Even if a community had a doctor, there was little that an overworked and minimally informed person could do.”

People, aged 25 to 45 years, were generally most susceptible.

“There is a theory that the stronger immune systems of young, healthy people basically reacted so strongly to the virus that their own immune systems killed them,” said Wagner. “This is happening right on the heels of the war, so as if the war hadn’t killed enough men of that age, the flu was going to kill more.”

Even if a community had a doctor, there was little that an overworked and minimally informed person could do.

– Trudy Cowan

Twenty-eight people died from the deadly virus in the Alliance area. Only two residents from the town proper died during the whole pandemic—Dr. Russel Boyle and postmaster, Mr. Art Smith. The remaining 26 who died resided in the country, said Alcorn.

About 25 families initially contracted the Spanish flu in the spring of 1919. The family of Alfred Smith lost six of its ten members, including children from three to 20 years of age in just a few days, as well as the 46-year-old mother, Carrie. Her husband and remaining three children recovered.

“They had a very small home, and I think it was very crowded,” Alcorn said. “[One] of the rules in those days … was to put [the sick] in a different room, but, in some of these rural houses, there wasn’t another room.”

One month after the spring outbreak, the community held a memorial service for those who died from the Spanish flu, back at the school where the second wave began.

Six Smith family headstones lay side by side in the hilltop cemetery—overlooking the village that’s tucked into a bend in the Battle River. They continue to be a tragic reminder of the pandemic’s devastation more than a century ago.

Today, social distancing is practised in the Alliance area when friends meet for coffee on patios and in driveways. Prior to the provincial Phase 1 opening in mid-May, only the bank, hardware store, grocery store, and restaurant (takeout only) were open.

Alcorn doesn’t wear a face mask herself, but does respect social distancing, and limits trips from her farm northwest of Alliance.

Wagner chuckles when she hears people say that “COVID is unprecedented.

“I say, ‘No, it’s really not. The similarity is quite eery.’”

— Lorena Franchuk

-

Did you enjoy this article?

Subscribe to the Rural Health Beat to get a positive article about rural health delivered to your inbox each week.

Oops! We could not locate your form.