It’s been over 100 years since the deadly Spanish Influenza pandemic hit Alberta, and it will be some time yet before we can truly evaluate how COVID-19 compares to the Spanish flu in terms of scope and intensity. Rural Health Beat asked historian, Suzanna Wagner, a University of Alberta history Master’s student, to compare what we know today about the response to the current pandemic, to that of the Spanish flu of a century ago.

Masks

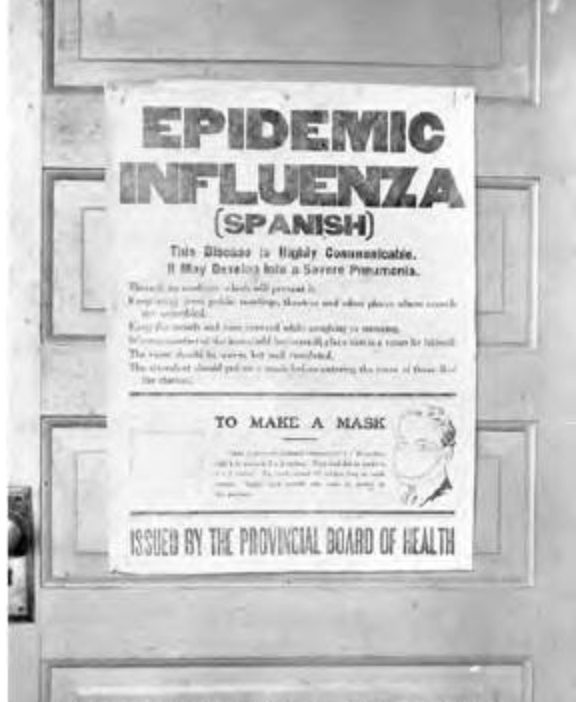

- Spanish flu: The Board of Health ordered citizens to wear masks in public. These masks could be purchased for 10 cents each. “It was not universally adhered to, even by physicians. There were debates about how effective [masks] were or weren’t,” says Wagner. Alberta photos from 1918-1919 show some people wearing masks. A poster by the Provincial Board of Health includes information on the illness and gives instructions on mask-making.

- Coronavirus: Early on, commercial masks were hard to come by for the average person as supplies were reserved for health-care workers. Many people started to craft their own designs. Alberta has not mandated the wearing of masks in public to date, but some businesses are now requiring them before customers can enter their premises.

Isolation

- Spanish flu: “Large groups were clearly a no-go … but [the social distancing] that we have now doesn’t really resonate in the newspapers … There was a discussion that ‘just because school is closed, doesn’t mean kids can play in the streets with other kids, because that’s how it’s going to spread.’”

- Coronavirus: Social distancing was encouraged early on with COVID-19. Maintaining a two-metre distance between people outside of the household was recommended.

Closures

Churches were closed during both pandemics.

- Spanish flu: Schools were closed and “restricted business hours were put in place. The idea that the shorter amount of time that business was open, the less likely that there was transmission. Retail people objected to this … saying ‘that doesn’t make any sense. If you reduce business hours, the same number of people are going to crowd in.’”

- Coronavirus: Non-essential businesses were required to close shortly after the virus arrived in the province. School facilities were closed with online learning occurring at home. Employees who were willing and able were encouraged to work from home. Most businesses that remained open reduced their hours.

Management/coordination

- Spanish flu: Some communities initially wouldn’t let outsiders inside the town’s limits. “That [restriction] was very short lived. It did not prove especially successful … [The virus was] thriving right at harvest time, [creating] significant economic problems and basic functioning-of-society problems.”The tragic consequences of the Spanish flu led to the Canadian Government’s creation of the Department of Health in 1919. The creation of the Alberta Department of Health came in the same year.

- Coronavirus: Restrictions were organized province wide (other than the reopening phase when the easing of restrictions in Brooks and Calgary were delayed by 1.5 weeks as compared to the rest of the province). Many municipalities shutdown local amenities such as playgrounds and public recreation centres, in line with provincial orders. International borders were closed by the federal government with allowances made for essential travel.

Reporting statistics

- Spanish flu: There were long delays in the reporting of case numbers, as many rural areas were short on physicians and rural physicians tended to cover large areas. When a doctor wasn’t involved, the cases were unlikely to be reported.About 31,000 cases of the Spanish flu were reported in Alberta during the fall/winter of 1918-1919, with a resulting 4,308 deaths before the pandemic subsided in May 1919. In 1918, Edmonton’s medical health officer reported 5,789 local cases of influenza, and 249 “imported” cases, which lumped together both rural Albertans visiting the city and travellers from farther abroad.(The numbers are estimates only as not all cases were reported and influenza was often recorded as the cause of death when a secondary ailment, such as tuberculosis or pneumonia, was responsible.)

- Coronavirus: At the height of the pandemic, Alberta held almost daily media conferences sharing up-to-date numbers of new, recovered, and active COVID-19 cases, as well as deaths. Alberta Health Services reported its cases numbers by zone online.

Promotion/advertising

- Spanish flu: Advertisers offered ways to cope with the pandemic such as buying a comfortable chair and bookshelf for all the new books people would read. One department store touted the benefits of telephone orders “since it’s your civic duty to your friends and neighbours to not spread the flu.”

- Coronavirus: As soon as shutdowns occurred, various media began encouraging social distancing, staying home, and broadcasting messages of hope. As time went on, advertising and public service announcements began to suggest ways to beat isolation blues with home decorating ideas, shopping online 24/7, craft and exercise ideas, and ordering curb-side takeout to help local restaurants stay in business.

Transmission

- Spanish flu: The Spanish flu likely arrived via ship and spread across the country by rail.

- Coronavirus: The coronavirus was initially brought to Canada through international air travel.

— Lorena Franchuk

-

Did you enjoy this article?

Subscribe to the Rural Health Beat to get a positive article about rural health delivered to your inbox each week.

Oops! We could not locate your form.