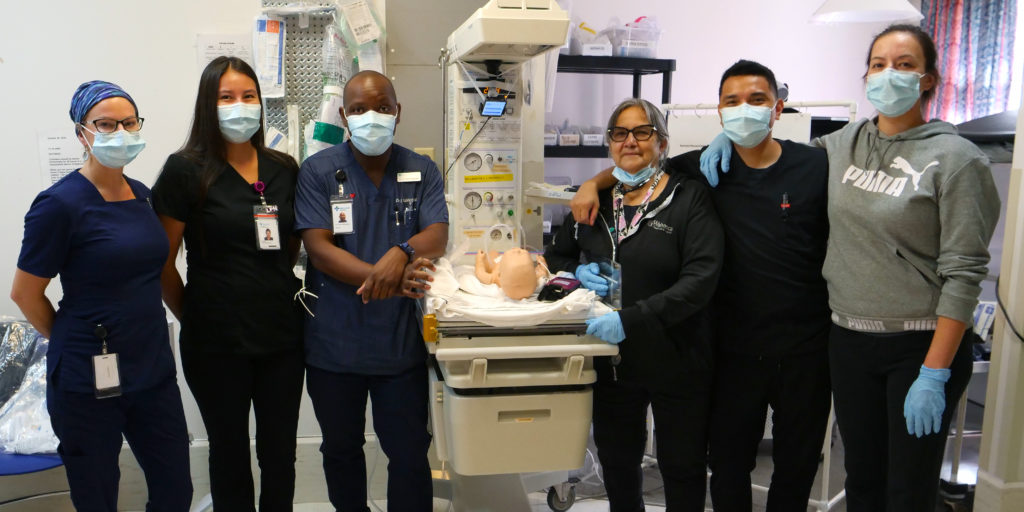

– Photo by Bobby Jones

Legendary musician and band leader, Duke Ellington, once said, “A problem is a chance for you to do your best.”

That’s exactly the approach the Wabasca/Desmarais Health Care Centre’s nursing team took in March 2020 when COVID-19 neared the doorstep of the community situated about four hours north of Edmonton.

COVID-19 shutdowns meant that the in-person training offered through Alberta Health Services (AHS) and others was suddenly unavailable.

Rather than go without training, especially in the midst of a pandemic, the team—lead by assistant head nurse, John Paolo Pana—decided to learn as much as possible about the virus to protect their patients and community, as well as themselves.

The Wabasca team was concerned how they would manage to treat patients if any of the limited number of staff caught COVID-19 themselves. Besides, most of their patients were friends and family they knew well in the tight-knit community.

“There [was] so much uncertainty, so much fear in the hospital, because you [didn’t] even know what COVID was,” recalled Pana of the pandemic’s early days.

After some thought, Pana, who is used to “MacGyvering” (a term referring to an ‘80s TV character who could solve problems using the limited and often unconventional resources at hand) decided the training could continue in a new format.

“Why can’t we still do the simulation; … why can’t we use technology?” he pondered.

“Why can’t we meet [the instructors] virtually instead? They don’t need to be there with us physically. We can still be in our hospital [and] we [can] perform the same [procedures].”

– Photo by Bobby Jones

For their virtual Zoom simulation training debut, Pana pulled out his own mobile phone and borrowed a colleague’s so the offsite facilitators could see exactly how the how the team performed from different angles in the various case studies.

In the first virtual session, health professionals learned how to safely don their personal protective equipment (PPE) for proper COVID protocol and carefully remove once the procedure was complete.

“[Staff were] able to see how frequently [they] would breach PPE protocols,” said Pana. “[The instructors] would say: ‘You touched your face. You touched your mouth,’ so we were able to learn our tendencies as well.”

COVID-19 awareness was the catalyst for the virtual simulations, but the group soon invited other health disciplines and community volunteers to help make the scenarios realistic. Wabasca’s retired fire chief even came out and was very convincing as a patient with a broken pelvis. A facilitator, who presents a case study, acted as a clinical advisor to update the team on the patient’s status based on the various staff interventions.

Eighteen months later, the team is comfortable with the switch to virtual learning. And despite still having COVID cases in the community, the team is confident they can deliver care without compromising themselves or those around them.

Pana has since upgraded some of the mobile phones to laptops and a projector, so it’s no longer necessary to tape his cell phone to an intravenous pole to capture the proper angle as the team prepares for simulations such as an intubation, a postpartum hemorrhage, or a massive casualty event.

The opportunity for health professionals to role play in their own hospital has proved invaluable to make sure the team is ready for any real-life situations, Pana said.

Wabasca’s former community medical director, Dr. Sharon Reece, participated in several of the virtual classes offsite as a facilitator.

Dr. Reece, who now works as an assistant professor at the University of Arkansas in the United States, noted that the debrief is the most important part of the exercise as everyone can discuss what went right or wrong and then brainstorm solutions.

“This was an example of a grassroots rural initiative that started rural, that was for rural, and benefited rural. There was support from higher resource areas, and there was involvement from those in urban centres, but I think it really challenges that assumption that things have to happen first in urban centres and then be rolled out into rural.”

– Dr. Sharon Reece on the virtual simulation training piloted in Wabasca

Since the virtual launch of this type of training in Wabasca, Dr. Reece has helped introduce the concept to other rural health regions across Canada. It wasn’t long before that COVID-19 training was put into practice by the health-care teams who had carried out their own simulations.

“Within hours of having that [virtual] training, two rural health-care teams in Alberta experienced their first real COVID patient who required intubation and [was] transferred to the [intensive care unit],” she said. “So, in terms of timeliness of education intervention, we’re talking in the span of a few hours before it [was used] on a real-life patient who [was] critically ill. That was amazing.”

Both Dr. Reece and Pana agree the virtual simulation option is here to stay.

“A lot of rural and remote teams are hungry for education, and they’re hungry for resources,” said Dr. Reece.

“So when something that is context specific is offered and it’s actually relevant, then there is a real need and a real receptiveness to that sort of education.”

The family doctor was so impressed by the Wabasca team’s commitment to continued learning and their ingenuity in putting it into practise, that she nominated them for an RhPAP Rhapsody Award. The team was eventually selected as a 2021 Rhapsody Health-care Heroes Award recipient.

“It’s a real testament to the strength of the nursing team in Wabasca, [to their love] for their work, their passion and teamwork, and [their] willing[ness] to embrace change in a time that was so uncertain,” Dr. Reece said during a recent Zoom interview from Arkansas.

“This was an example of a grassroots rural initiative that started rural, that was for rural, and benefited rural. There was support from higher resource areas, and there was involvement from those in urban centres, but I think it really challenges that assumption that things have to happen first in urban centres and then be rolled out into rural.”